Stones and Other Stuff

A Matter of Concern to Theory of History

LISA REGAZZONI • JULY 2022

This ONE MORE THING… entry is connected to Lisa Regazzoni’s “Unintentional Monuments, or the Materializing of an Open Past,” which first appeared in our June 2022 issue.

Cite this post: Lisa Regazzoni, “Stones and Other Stuff: A Matter of Concern to Theory of History,” One More Thing… (blog), History and Theory, July 2022, https://historyandtheory.org/omt/2022-regazzoni.

Join the conversation

Check out the History and Theory Discord server, where we have a dedicated channel for discussing contributions to One More Thing . . . !

What does a statue of Louis XIV in an engraving published in 1689 have in common with stone artifacts in an engraving published in 1740?

The designation.

In the initial decades of the eighteenth century, both species of artifacts were indeed referred to as “monuments.” Under close scrutiny, this name sharing even morphs, surprisingly, into a paradox. Illuminated, the latter acts as a prism, laying bare a spectrum of questions and reflections on history as historiography: on its nature and function as well as on its epistemic assumptions and values, all of which, as I argue in my article, continue to play latent roles in historiography today.

Let’s examine the illustrations closely.

Figure 1: Nicolas Guérard Vue de la place des Victoires, published in Claude-François Ménestrier, Histoire du roy Louis le Grand par les medailles (Paris: Jean-Baptiste Nolin, 1689) Source: Gallica/BnF.

Figure 1 is a contemporary engraving of a Louis XIV statue created by the sculptor Martin Desjardins for the new Place des Victoires in Paris. The monument itself was unveiled on 28 March 1686 and demolished by the revolutionaries in 1792 following the abolition of the monarchy. The engraving shows the king in coronation robes with Victory crowning him from above with a laurel wreath. He is holding the scepter like a cane, pointed downward, and trampling on a three-headed Cerberus, which is probably an allegory of the defeated Triple Alliance of the 1670s (Spain, Holland, and the Holy Roman Empire). On the marble pedestal we see one of the four bronze relief plates idealizing Louis XIV’s major political and military deeds between 1662 and 1679. At the base in bronze are two of the four captives of different ages and facial expressions, an allegorical representation of the nations defeated by Louis XIV (Spain, Holland, the Holy Roman Empire, and Brandenburg-Prussia) and a portrayal of the various sentiments of the vanquished: hope, revolt, resignation, despondency. The monument was erected “to posterity” and, as stated in one of the numerous inscriptions engraved on the pedestal, in “everlasting memory” of the king’s achievements.

Figure 1, detail.

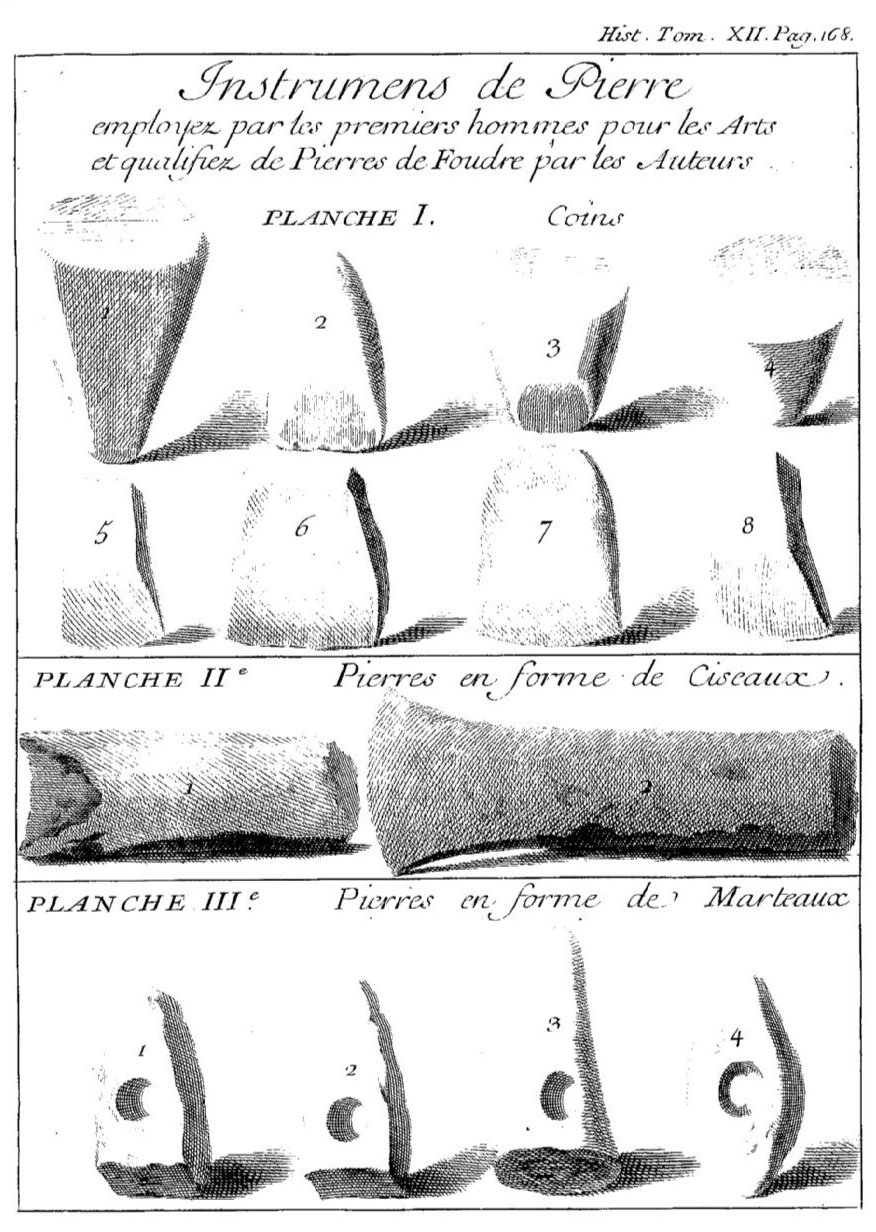

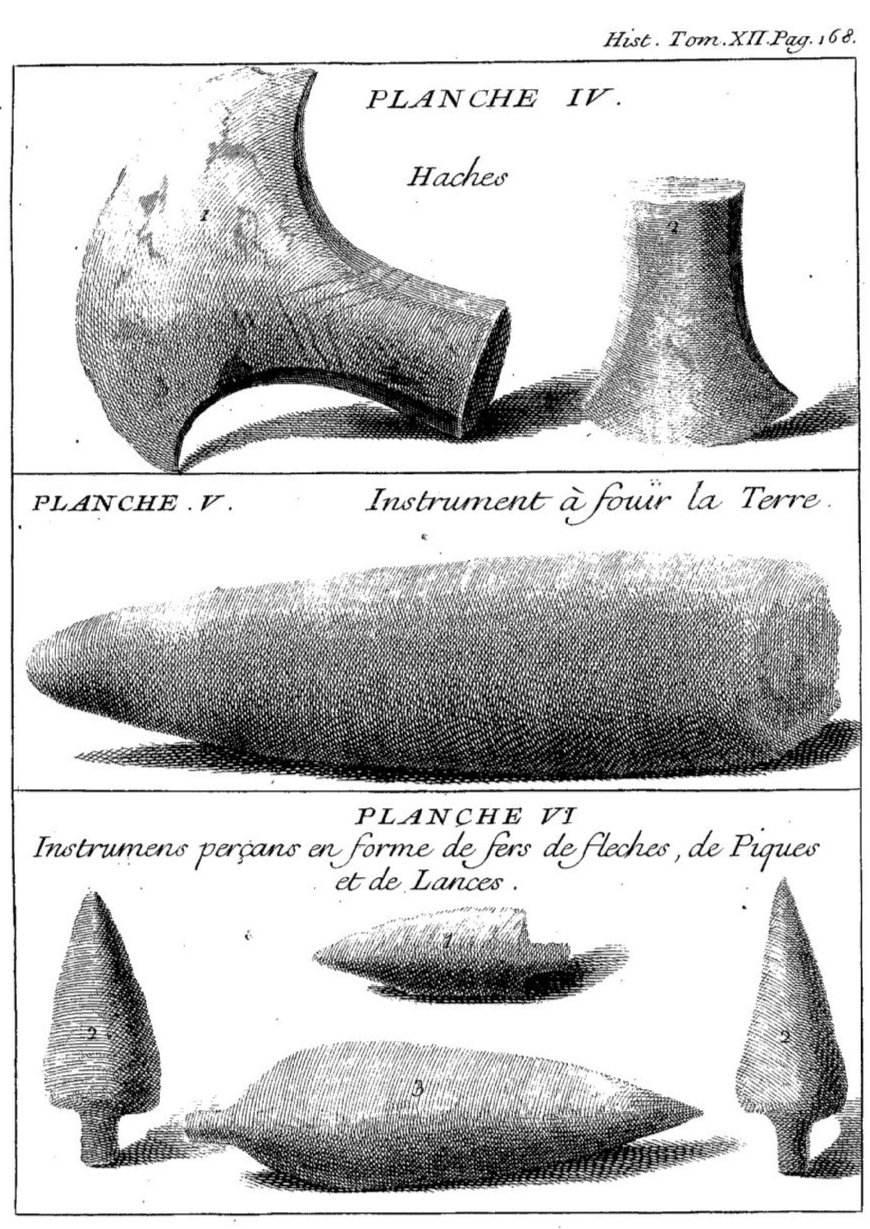

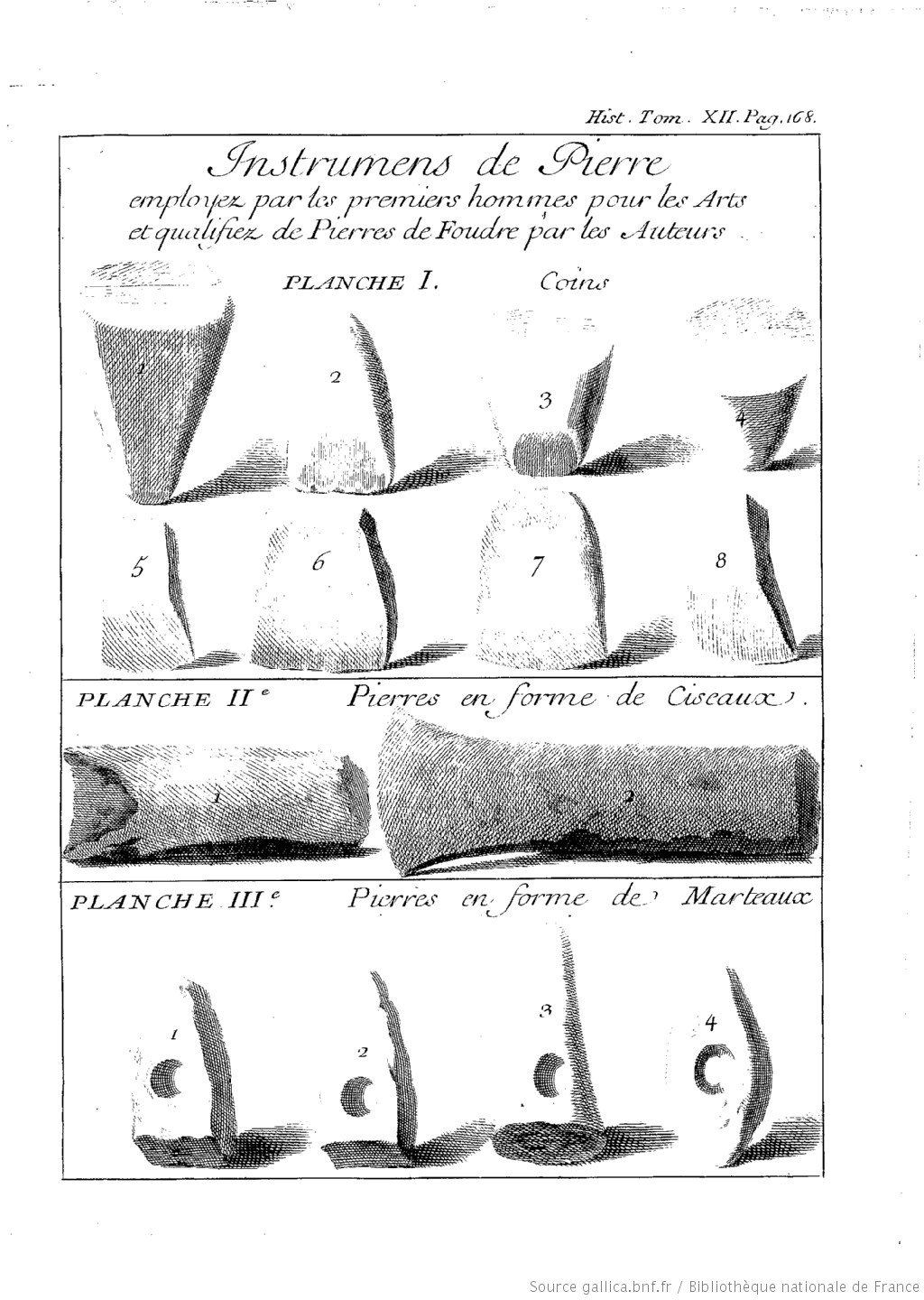

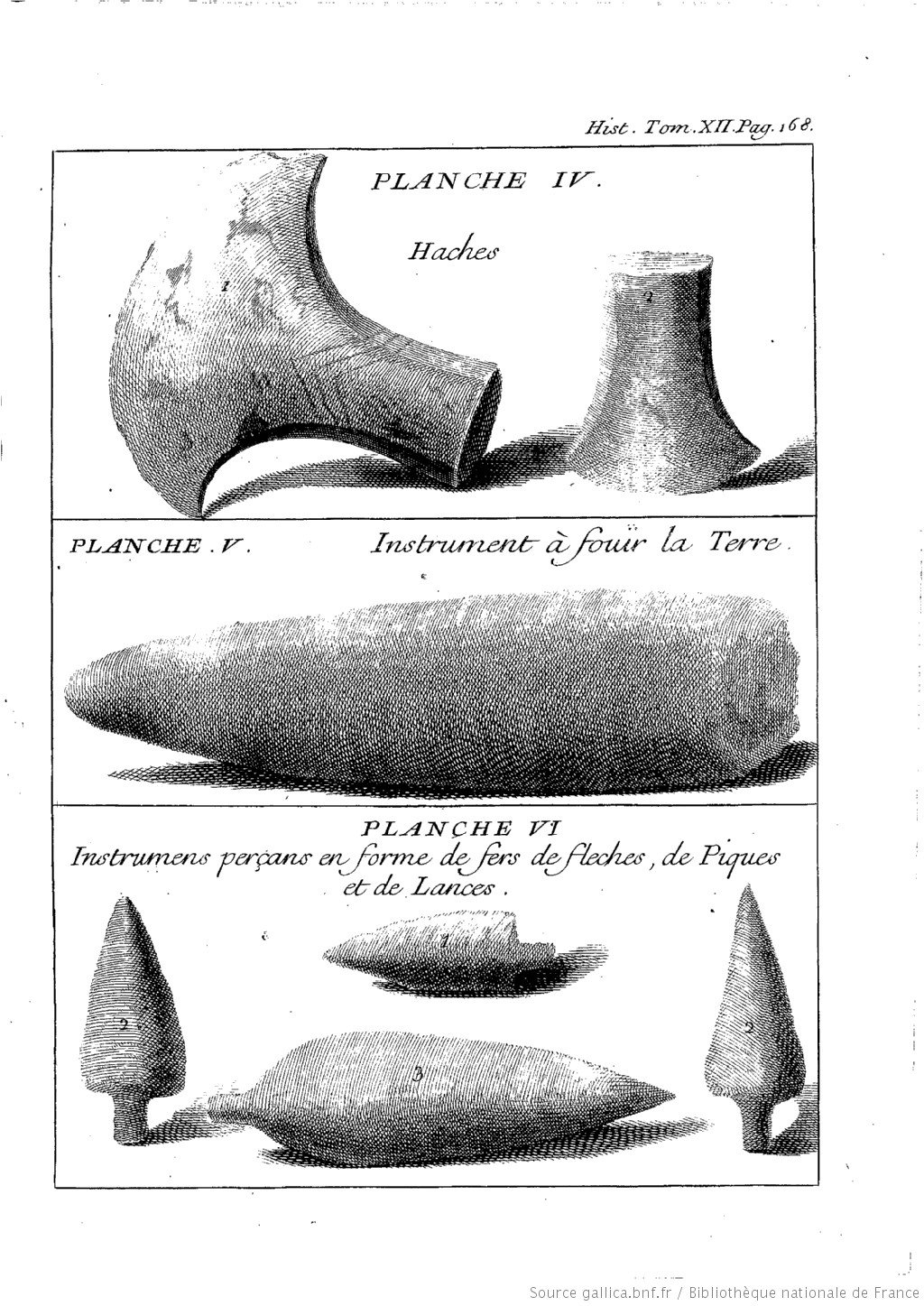

Figures 2 and 3, in contrast, show some of the first engravings of stones as artifacts in a French publication. The engravings, which were commissioned by the antiquarian Nicolas Mahudel, are reproductions of stone objects belonging to various curiosity cabinets and of drawings and artifact engravings he had not inspected directly. Up until the beginning of the eighteenth century, these stones, or “thunderbolts” (pierres de foudre), were generally considered to be solidified lightning bolts that had come into contact with cold air (fig. 4). But it wasn’t until the eighteenth century that French naturalists and antiquarians, including Mahudel, began to consider them as “monuments” of the oldest human activity. The two plates (fig. 2 and 3) reproduce the classification system of stone artifacts elaborated by Mahudel and are the result of a complex comparative practice. The morphological similarity he observed between thunderbolts and ancient brass or iron tools found in the subsoil or the burial mounds scattered on French soil led him, in 1734, to the conclusion that, although made of different materials, they belonged to the same category of tools and dated back to different periods of human history (based on Lucretius’s theory of a chronological order of materials used by humankind, according to which stone tools were older than bronze tools, and these in turn preceded tools made of iron). This deduction was further corroborated by a comparison of the stones with a number of stone tools brought back from the “New World,” where, according to French travelers, they served as arrows, knives, and axes. Hence, stone or bone artifacts of the spatially distant “savages” of the “New World” shed light on the true nature of thunderbolts: no longer considered natural products, they were instead regarded as evidence of the activity of temporally distant European “savages”—in this case, the Celts. Recognized as anthropogenic products, stone tools came to be regarded as testimonies of the oldest human history.

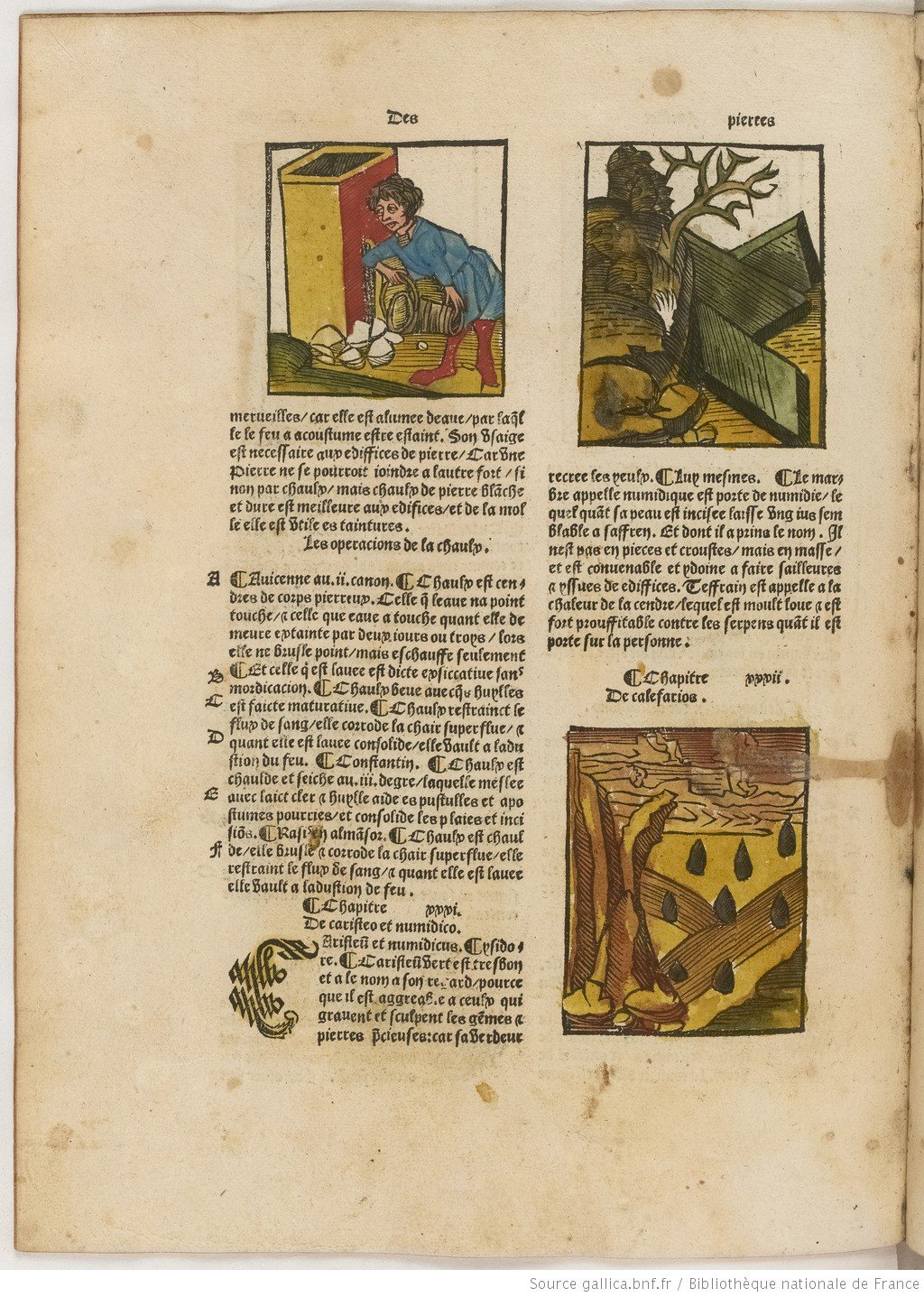

Figure 4: Illustration of the thunderbolts, in Johann Wonnecke von Kaub, Ortus sanitatis (Paris: Antoine Vérard, 1499–1502). Source: Gallica/BnF.

Be that as it may, what does the glorified depiction of a monarch and his deeds intended for future generations have in common with stone artifacts, objects of everyday use with no commemorative value? What is the common denominator of artistic-monumental compositions with a complex sculptural and iconographic program that is almost totally devoid of a mimetic relationship with historical reality and reproductions of rudimentary tools that are decontextualized and reorganized in a classificatory table? Or, for that matter, of encomiastic inscriptions, on the one hand, and numbers and concise descriptions of different forms and uses, on the other? Why were they both recognized as “monuments,” though one was a highly partisan version of history deliberately intended by the makers (such as clients or artists) and the other consisted of remains as unwitting evidence of historical information that may originally have been unintended by their makers? Why is it significant that one became an object of study in the history of art or the history of political discourse and propaganda and the other became an object of study in the history of modern antiquarianism or the history of archaeology and historical epistemology?

This shared designation as “monuments” appears even more contradictory to today’s readers given that the term was frequently employed as a synonym for authentic and truthful testimony and evidence, particularly in the heated debate around the reliability of history and its knowledge value. At one and the same time, the monument indeed designated a biased representation of history and the antidote to the interest-led partisanship of historiographers.

If this definition of “monument” seems hybrid and intrinsically contradictory, it is because theoretical reflection on the historical method, notably in the nineteenth century, introduced a clear distinction between the artifact reproduced in figure 1 and the artifacts reproduced in figures 2, 3, and 4. This reflection, based on the category of intentionality, made them objects with different functions and epistemic values, depending on whether they had been produced intentionally to inform posterity about the past (or present) or had survived into the present without any memorial intention and been employed regardless as witnesses of some fact or condition of the past.

The stone items reproduced here and the other types of material and immaterial “monuments” that I discuss in my article are part of a brief outline of what we might call the history of the epistemology of “evidence” articulated around the category of intentionality (and unintentionality). In my opinion, this is a category that, although withdrawn from epistemological reflection, continues nolens volens to survive underground and act implicitly in historical research—or, perhaps, even one that has hitherto allowed us to think of the past as an open and ever-expanding territory.

And all this from just posing a simple question: What constituted a monument?